Hours of Operation

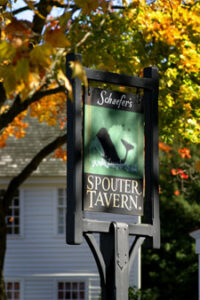

The new and improved Spouter’s Tavern is now open!

Friday – Sunday

11 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Enjoy a riverside lunch at Schaefer’s Spouter Tavern, which is located in the heart of the Museum’s seafaring village alongside the 1841 whaleship Charles W. Morgan.

19th-Century Taverns

19th-Century Taverns

Nineteenth-century seaport taverns were the homes to an ever-changing population of sailors who spent a few days of freedom ashore before shipping for another voyage.

Seaport taverns varied in size and refinement. More elegant establishments, such as the coffee houses of the early 19th century and fine hotels of the later years, catered to the influential members of the community like ships’ captains, merchants and politicians. Thus, these inns often served as the seat of local business and politics.

Lower on the scale was the cheap dive or grog shop. Often attached to sailors’ boarding houses, they saw many a shore-side spree during which “Jack Tar” might well be bilked out of his money by crimps, boarding house masters and other “landsharks.”

Though named for the tavern in Melville’s Moby-Dick (see below), Schaefer’s Spouter Tavern is a re-created exhibit, built by the Museum in 1956. However, the woodwork in its main room, including doors, windows, floor, wainscoting, bar, benches and fireplace, comes from the Central House Inne in Stoddard, New Hampshire, built in 1833. The hideaway bed in the corner was for a hired barman, who slept there to admit late travelers, and also to keep an eye on the supplies.

“The Spouter-Inn” — from Moby-Dick chapter three

“Entering that gable-ended Spouter-Inn, you found yourself in a wide, low, straggling entry with old-fashioned wainscots, reminding one of the bulwarks of some condemned old craft. On one side hung a very large oil painting so thoroughly besmoked, and every way defaced, that in the unequal crosslights by which you viewed it, it was only by diligent study and a series of systematic visits to it, and careful inquiry of the neighbors, that you could any way arrive at an understanding of its purpose.

The opposite wall of this entry was hung all over with a heathenish array of monstrous clubs and spears. Some were thickly set with glittering teeth resembling ivory saws; others were tufted with knots of human hair; and one was sickle-shaped, with a vast handle sweeping round like the segment made in the new-mown grass by a long-armed mower. You shuddered as you gazed, and wondered what monstrous cannibal and savage could ever have gone a death-harvesting with such a hacking, horrifying implement. Mixed with these were rusty old whaling lances and harpoons all broken and deformed. Some were storied weapons. With this once long lance, now wildly elbowed, fifty years ago did Nathan Swain kill fifteen whales between a sunrise and a sunset. And that harpoon — so like a corkscrew now — was flung in Javan seas, and run away with by a whale, years afterwards slain off the Cape of Blanco.

Crossing this dusky entry, and on through yon low-arched way — cut through what in old times must have been a great central chimney with fireplaces all round — you enter the public room. A still duskier place is this, with such low ponderous beams above, and such old wrinkled planks beneath, that you would almost fancy you trod some old craft’s cockpits, especially of such a howling night, when this corner-anchored old ark rocked so furiously. On one side stood a long, low, shelf-like table covered with cracked glass cases, filled with dusty rarities gathered from the wide world’s remotest nooks. Projecting from the further angle of the room stands a dark-looking den — the bar — a rude attempt at a right whale’s head. Be that how it may, there stands the vast arched bone of the whale’s jaw, so wide, a coach might almost drive beneath it. Within are shabby shelves, ranged round with old decanters, bottles, flasks; and in those jaws of swift destruction, like another cursed Jonah (by which name indeed they called him), bustles a little withered old man, who, for their money, dearly sells the sailors deliriums and death…

I sat down on an old wooden settle, carved all over like a bench on the Battery. At one end a ruminating tar was still further adorning it with his jackknife, stooping over the diligently working away at the space between his legs. He was trying his hand at a ship under full sail, but he didn’t make much headway, I thought.

At last some four or five of us were summoned to our meal in an adjoining room. It was cold as Iceland — no fire at all — the landlord said he couldn’t afford it. Nothing but two dismal tallow candles, each in a winding sheet. We were fain to button up our monkey jackets, and hold to our lips cups of scalding tea with our half frozen fingers. But the fare was of the most substantial kind — not only meat and potatoes, but dumplings; good heavens! dumplings for supper! One young fellow in a green box coast, addressed himself to these dumplings in a most direful manner…

A trampling of sea boots was heard in the entry: the door was flung open, and in rolled a wild set of mariners enough. Enveloped in their shaggy watch coats, and with their heads muffled in woolen comforters, all bedarned and ragged, and their beards stiff with icicles, they seemed an eruption of bears from Labrador. They had just landed from their boat, and this was the first house they entered. No wonder, then, that they made a straight wake for the whale’s mouth — the bar — when the wrinkled little old Jonah, there officiating, soon poured them our brimmers all round.”

Moby-Dick (1851), chapter three — Herman Melville